Enhancing PicoRV32 Performance: Leveraging Internal Registers for I/O Operations

Integrating LSRAM and PicoRV32: Initial Challenges

After successfully integrating LSRAM with the PicoRV32, initial simulations revealed significant latency between instruction fetches and output reflection. The PicoRV32, while efficient in size, is not optimized for performance, leading to a delay of about six clock cycles for the CPU to write data to I/O or memory—twice the time it takes to write to its internal registers. These internal registers are mainly used for temporary data, with their access managed entirely by the compiler.

Exploring the RV32E Extension

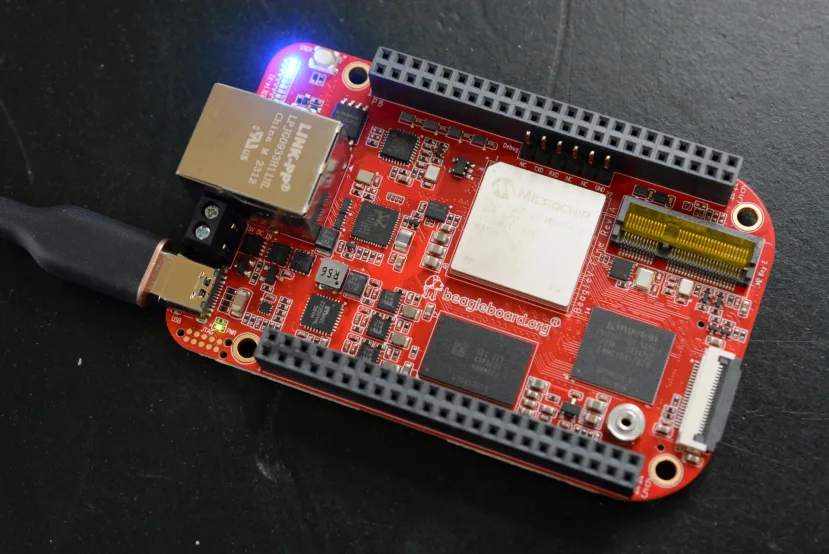

During early discussions, a BeagleBoard community member suggested using the RV32E extension, which only enables the first 16 of the CPU’s 32 internal registers. This approach was initially set aside due to concerns about accessing these registers via the inline assembly feature in compilers. However, the observed latency led us to revisit the RV32E extension, aiming to access these registers through defined macro functions via inline assembly.

Mapping I/O to Internal Registers

To align with a more performance-oriented design similar to TI’s PRU-ICSS, where I/Os are mapped to specific registers, I decided to map the I/Os to the x30 and x31 registers of the PicoRV32’s internal register set. This required designing a new I/O controller to manage data transfers between these internal registers and the I/O, as internal register file transfers differ significantly from external memory operations.

The Limitations of RV32E

Upon implementing these changes, I compiled a simple LED control program using the RV32E extension with the GCC compiler. It became apparent that the RV32E extension would completely block the use of the last 16 internal registers, including the x30 and x31 registers, even in inline assembly. This limitation rendered the RV32E architecture unsuitable for our needs, as it restricted access to registers we intended to use for I/O operations.

Returning to RV32IM and Overcoming Compiler Challenges

With the RV32E approach ruled out, we reverted to the standard RV32IM extension, which allows the use of all 32 registers. The challenge then was to prevent the compiler from using the x30 and x31 registers for temporary data storage, which would inadvertently write to the I/O.

This is where the -ffixed-xN flag in the compiler came into play. This flag prevents the compiler from using specified registers, allowing us to reserve x30 and x31 exclusively for I/O operations. However, a careful examination revealed that this flag only prevents the use of temporary registers and does not affect other registers such as the global pointer or stack pointer.

Understanding RISC-V Calling Conventions

The RISC-V calling convention outlines the usage of different registers in a RISC-V system:

| Register | ABI Name | Description | Saver |

|---|---|---|---|

| x0 | zero | Hard-wired zero | — |

| x1 | ra | Return address | Caller |

| x2 | sp | Stack pointer | Callee |

| x3 | gp | Global pointer | — |

| x4 | tp | Thread pointer | — |

| x5–7 | t0–2 | Temporaries | Caller |

| x8 | s0/fp | Saved register/frame pointer | Callee |

| x9 | s1 | Saved register | Callee |

| x10–11 | a0–1 | Function arguments/return values | Caller |

| x12–17 | a2–7 | Function arguments | Caller |

| x18–27 | s2–11 | Saved registers | Callee |

| x28–31 | t3–6 | Temporaries | Caller |

Understanding this convention was crucial in navigating the limitations of the -ffixed-xN flag and ensuring that x30 and x31 could be reliably used for I/O without interference from the compiler.

Conclusion

While the initial approach using the RV32E extension proved unfeasible, reverting to RV32IM and leveraging compiler flags provided a workable solution to manage I/O through internal registers. This experience underscores the importance of understanding both the hardware architecture and the compiler’s behavior when optimizing for performance in embedded systems.

By carefully managing register usage, we were able to improve the I/O performance of the PicoRV32, bringing us closer to a more efficient design akin to TI’s PRU-ICSS. This solution also maintains the flexibility to revert to a memory-mapped I/O approach if needed, ensuring that the system remains adaptable to future requirements.

References